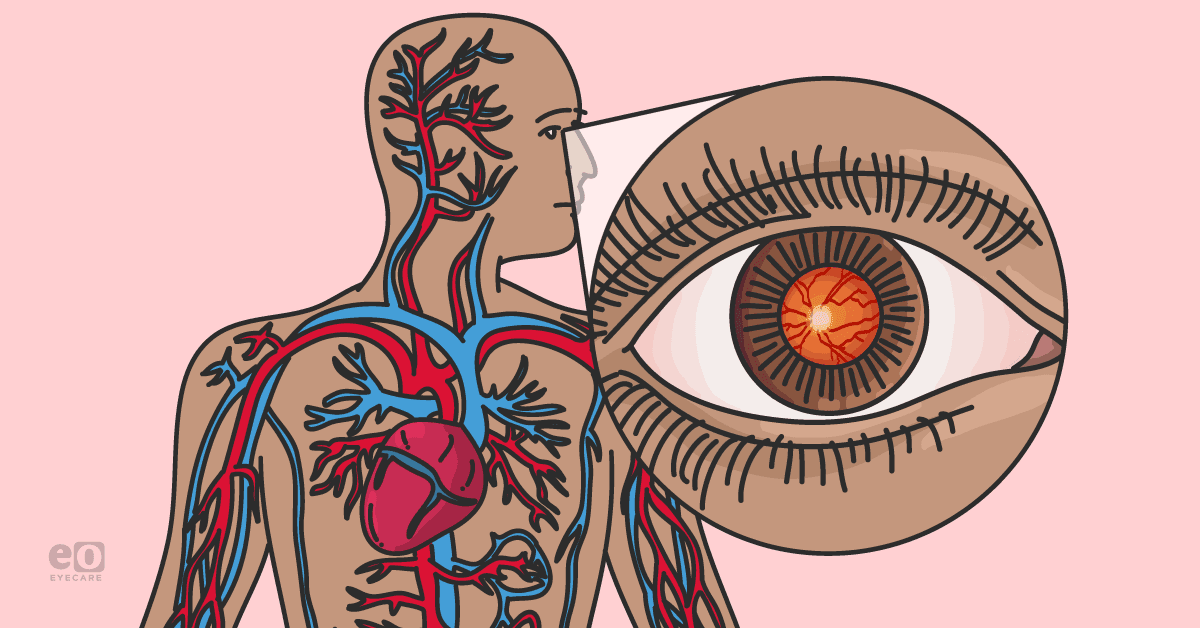

The human body is an intricate network of interconnected systems, and often, the health of one system can significantly impact the function of another.

Ocular manifestations resulting from systemic infections exemplify this interplay between bodily systems. The eyes, often considered the windows to one’s health, can also provide valuable insights into the various body systems.

Systemic infections, whether bacterial, viral, fungal, or parasitic in origin, can affect the eyes in various ways, highlighting the importance of understanding these manifestations for early diagnosis and appropriate management.

Understanding systemic infections

Systemic infections are those that affect the entire body rather than being localized to a specific organ or region.

These infections can enter the body through various routes, including the respiratory, gastrointestinal, or genitourinary systems, and they can spread through the bloodstream, lymphatic system, or direct extension from adjacent tissues.

Download the ocular manifestations of systemic infections cheat sheet here

📝

Systemic Infections and Ocular Manifestations: A Concise Overview

This downloadable guide describes the ocular manifestations of systemic infections that ophthalmologists are likely to encounter, along with pearls for diagnosing and treating the infections.

Viral systemic infections and their ocular manifestations

Herpesviruses

Herpesviruses, such as herpes simplex virus (HSV) and varicella-zoster virus (VZV), can cause ocular manifestations. HSV can lead to herpetic keratitis, an inflammatory eye condition that can result in corneal scarring if left untreated.1 Herpes simplex keratitis is an infection due to reactivated HSV-1 from the trigeminal ganglion.

Clinical features include eye redness and eye pain, foreign body sensation, and photophobia.1 These symptoms present similarly to viral conjunctivitis but are typically unilateral.

Diagnosing herpes simplex keratitis is performed via fluorescein staining; the stain will show superficial corneal erosions, also known as dendritic ulcers, that resemble the branches of a tree.1

Herpes simplex keratitis

Herpes simplex keratitis can affect either the stromal or endothelial part of the cornea. The stroma is the thick middle layer of the cornea. Stromal involvement is characterized by inflammation and the formation of immune infiltrates within the corneal stroma. Stromal keratitis is often associated with a prior history of recurrent epithelial herpes simplex keratitis.

Clinical features include stromal edema, necrosis, and the characteristic branching dendritic ulcer mentioned previously. Necrotizing stromal keratitis is characterized by a creamy white necrotic mass inside the corneal stroma and may vary in thickness. It is often associated with corneal thinning, vascularization, and ocular perforation.2

The majority of patients will experience severe pain and low vision, and the disease has a course of anywhere from 2 to 12 months. Necrotizing stromal keratitis appears to be due to the body’s heightened immune response to viral material that has penetrated the deep stroma.

Herpesvirus can insert glycoproteins into the host membrane, which makes the virus’ antigen unfamiliar to the body. This is what drives the chronic autoimmune reaction we see in the disease.2

HSV endotheliitis

On the other hand, endothelial involvement in herpes simplex keratitis is less common than stromal involvement. The endothelium is the innermost layer of the cornea responsible for maintaining corneal transparency; it achieves this by regulating fluid balance. Endotheliitis is defined as an inflammation of the corneal endothelium due to keratic precipitates.

Primary endotheliitis is when inflammation starts in the endothelium, and secondary endotheliitis is when inflammation spills over from structures such as the cornea and anterior chamber. This condition can affect a specific region of the endothelium, causing focal stromal edema, or may involve the entire endothelial layer, which leads to generalized bullous keratopathy.

Endothelial involvement is characterized by inflammation, swelling, and potential compromise of endothelial function. This can lead to decreased corneal clarity and visual acuity.

Treatment of HSV endotheliitis

Endotheliitis caused by HSV typically responds to corticotherapy for 30 to 45 days, making it plausible that the condition is caused by an immunological reaction to the invading agent’s substance. Cases refractory to steroids can be treated by antiviral therapy for about 10 days.

Treatment includes topical trifluridine solution or ganciclovir 0.15% gel.1 In the event that topical treatment cannot be applied, an oral antiviral such as acyclovir may be used instead.

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus

VZV, responsible for chickenpox and shingles, can cause herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO), leading to painful eye involvement. VZV is a double-stranded DNA virus that typically invades the upper portion of the respiratory tract via respiratory droplets containing the virus.

Here, it will replicate and further invade adjacent lymph nodes. The virus then spreads and progresses to a secondary cutaneous infection in about 1 week, and vesicles may erupt days later. After the primary infection has resolved, the virus enters a retrograde pathway along axons toward sensory nerve ganglia, entering a dormant phase.3

HZO is due to the reactivation of VZV in the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve and can occur in 10 to 20% of herpes zoster cases.3 Patients with HZO commonly present with prodromal pain distributed in the unilateral V1 area, accompanied by an erythematous vesicular rash. The pain is typically described as neuropathic, and patients may complain of a burning or shooting sensation.

The rash may also be preceded by systemic symptoms such as fever, headache, and malaise. If the nasociliary nerve is involved, there is a possibility of severe intraocular infection.3 A key physical exam finding to look out for is the Hutchinson’s sign, which is characterized by herpetic lesions around the tip of the nose.4

An ophthalmologist should be consulted urgently as this is a vision-threatening condition. VZV may be treated with the same antivirals as HSV, including ganciclovir gel or oral acyclovir.3 The typical dosing regimen includes acyclovir 800mg orally five times per day for at least 7 days.

Figure 1 demonstrates a patient with Hutchinson’s sign, which is characterized by herpetic lesions around the tip of the nose.4

Figure 1: Courtesy of Governator et al.

HIV/AIDS

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can affect the entire body, including the eyes. Ocular complications may include cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis—a sight-threatening condition. CMV retinitis may present in a patient complaining of floaters, photopsia, and visual field defects.5

Fundoscopy shows a “pizza-pie” appearance, characterized by retinal hemorrhages, granular white opacities around retinal vessels that resemble cotton-wool spots, and retinal detachment.5 Serological testing includes the presence of immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies and a four-fold increase in the levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies.5

Bacterial infections and associated ocular manifestations

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) can lead to uveitis, a type of inflammation in the middle layer of the eye, affecting the uvea. Ocular TB may mimic other eye diseases, making diagnosis challenging.

TB usually causes posterior uveitis, which affects the vitreous body, choroid, and retina.6 Clinical manifestations include painless visual disturbances, such as floaters, scotomata, and decreased visual acuity.

Diagnostics include an ophthalmic exam, in which leukocytes may be present in the vitreous humor and vitreous opacity.6 Additionally, tests for systemic diagnosis include acid-fast bacilli microscopy and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT).6

There can also be a foci of inflammation of the choroid and or retina. Complications include visual field loss due to scarring and major loss of visual acuity if the macula is involved.6

Lyme disease

Lyme disease, caused by Borrelia burgdorferi, can result in various ocular manifestations, including retinal vasculitis, keratitis, iridocyclitis, and uveitis.7 Lyme disease is commonly contracted in the Northeast region.

The early stage (Stage 1) of the disease presents with erythema migrans, a slowly expanding red ring around the tick bite site with central clearing; this is also known as a bull’s eye rash.7 Stage 2 is when ocular manifestations develop, which occur 3 to 10 weeks after the tick bite.7

Other signs and symptoms include migratory arthralgia, peripheral facial nerve palsy, and cardiac arrhythmia.7 Within each stage of Lyme disease, there are ocular manifestations that may be noted. During the first week of infection, patients may be affected by nonspecific self-limited follicular conjunctivitis. Photophobia and periorbital edema have also been reported.7

In the early disseminated stages, keratitis, idiocyclitis, vitritis, multifocal choroiditis, exudative retinal detachment, and panophthalmitis have been reported.8 Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations include optic neuritis, disc edema, and oculomotor palsy.8

Laboratory criteria for diagnosing Lyme disease positive IgM or IgG antibodies to B. burgdoferi in serum. IgM antibodies are present after 2 weeks and peak at 2 months.8

Don't forget to check out the ocular manifestations of systemic infections cheat sheet

Fungal infections and associated ocular manifestations

Fungal infections can affect the eyes, particularly in immunocompromised individuals. Patients taking immunosuppressants or those diagnosed with HIV/AIDS are at increased risk of candidal infections.

Mucocutaneous candidiasis presents with skin and nail infections, such as erythematous patches and satellite lesions. Oral thrush is also a sign of candidal infections and can be scraped off the tongue.

Candida endophthalmitis

Candida esophagitis is an AIDS-defining illness and presents with odynophagia. Systemic candidiasis can present with endophthalmitis, which is inflammation of the vitreous humor, the innermost layer of the eye.9

Cataract surgery is the most common cause of post-operative endophthalmitis, as Candida is able to invade exogenously.9 Hematogenous spread occurs via the presence of distant infection, leading to fungemia, then seeding of the vascular choroid by Candida, and finally, the spread of the infection to the retina and vitreous.9

Figure 2 is a fundoscopic image of candidal endophthalmitis, characterized by white fluffy infiltrates.10

Figure 2: Courtesy of Retina Image Bank.

Ocular and systemic symptoms of endophthalmitis are typically nonspecific; patients may complain of ocular pain, redness, swelling, and systemic symptoms such as malaise, nausea, and loss of appetite.11

In one study, 19% of patients with Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess first visited an ophthalmologist for ocular symptoms.11 This is why it is of utmost importance for ophthalmologists to be aware of these symptoms and signs and remain suspicious for systemic infection.

Ocular manifestations of parasitic infections

Toxoplasmosis

Toxoplasmosis, caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii, can lead to chorioretinitis, an inflammatory condition affecting the retina.12 Chorioretinitis presents with defects in the visual field at the site of inflammation, pain, and optic atrophy or macular scar formation, which can progress to blindness.12

Retinochoroiditis juxtapapillaris, aka Jensen disease, is characterized by visual field defects caused by retinochoroidal lesions adjacent to the optic disc.12 Fundoscopy of acute toxoplasmosis shows yellow-white retinal lesions, marked vitreous reaction, and concomitant vasculitis.12

Figure 3 is a fundoscopic image of toxoplasmosis chorioretinitis, characterized by yellow-white retinal lesions.13

Figure 3: Courtesy of Sudharshan et al.

Congenital toxoplasmosis can also result in eye abnormalities in newborns. Patients can remain asymptomatic for several years and then present with symptoms in the second through fourth decades of life.14 During the inactive stage of toxoplasmosis, the disease can present as quiescent atrophic chorioretinal scars; these scars present as pigmented lesions in clusters.

In the active phase, toxoplasmosis may present as necrotizing chorioretinitis with overlying vitritis. Fundoscopy will show a yellow-white lesion with indistinct margins; this is classically described as a “headlight in a fog” appearance.14

Diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of systemic infections

Early diagnosis and appropriate management of ocular manifestations resulting from systemic infections are crucial to prevent vision loss and systemic complications. Ophthalmologists and infectious disease specialists work together to identify the underlying infection and formulate a treatment plan. Diagnostic tools such as slit lamp examinations and imaging (e.g., optical coherence tomography/fundoscopic imaging) are essential in determining the cause of ocular manifestations.

Treatment typically involves addressing the underlying infection with antiviral, antibacterial, antifungal, or antiparasitic medications, depending on the pathogen. Inflammatory conditions like uveitis may require corticosteroids or immunosuppressive drugs to control inflammation.

Preventing systemic infections with ocular manifestations involves a multitude of measures, including getting vaccinated against viral diseases like herpes zoster and maintaining overall good health to reduce the risk of immunosuppression. Additionally, practicing good hygiene, especially during flu seasons, can help prevent the spread of infectious agents that could affect the eyes.

Conclusion

Ocular manifestations resulting from systemic infections underscore the interconnectedness of our various body systems. Timely recognition and management of these manifestations are vital not only for preserving vision but also for addressing the underlying systemic health issues.

Healthcare professionals and patients alike should be vigilant in recognizing and addressing ocular symptoms as part of a comprehensive approach to overall health and well-being. After all, the eyes are not just windows to the soul but also to our systemic health.