WHAT YOU'LL LEARN

The major causes and etiologies of uveitis

Pearls associated with uveitis and intraocular inflammation

Essential diagnostic considerations in the workup of uveitis

Introduction and Terminology

Uveitis, a term used to describe inflammation inside the eye, is often one of the more challenging diagnostic and treatment areas encountered by ophthalmology residents and fellows. Although uveitis can result from autoimmune diseases and infectious processes, nearly half of cases are idiopathic with no known attributable cause. Management of both acute and chronic inflammation require both systemic and ocular workup and timely treatment is essential to minimize vision loss. The myriad of complex presentations represent challenging cases for ophthalmologists at all levels and successful outcomes require an approach that addresses all possible relevant causes. Here, I present a modern approach to the diagnosis and management of uveitis.

Terminology

Terminology has links to etiology and clinical evolution and thus is relevant to any approach for the diagnosis and management of uveitis. Specifically, ophthalmology residents need to be aware of the following nomenclature.

- Onset: sudden versus insidious

- Duration: limited (less than 3 months) versus persistent (3 months or more)

- Course: acute versus recurrent (episodes separated by at least 3 months of inactivity) versus chronic (relapse occurring less than 3 months between episodes). Note that recurrent uveitis implies there was at least a 3 month period of inactivity between inflammatory episodes.

- Anterior chamber reaction requires a standardized grading of cells to ensure accurate description of disease duration and course:

- 0.5+ = 1-5 cells per high power field (HPF)

- 1+ = 6-15 cells/HPF

- 2+ = 16-25 cells/HPF

- 3+ = 26-50 cells/HPF

- 4+ = more than 50 cells/HPF

Differential diagnosis and red flags

Lesson 1: Rule out infections

When considering a uveitic diagnosis, the top priority is to rule out infectious process!

Figure 1: A patient presenting with progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) viral retinitis with a known history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) secondary to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Uveitis secondary to infectious processes can present as follows:

- Bacterial: usually acute and associated with recent intraocular penetration (e.g., surgery, trauma).

- Herpes viruses (herpes simplex, varicella zoster, cytomegalovirus): retinal as well as anterior chamber involvement.

- Syphilis, Lyme disease and tuberculosis are great masqueraders and may mimic any presentation; consequently, these 3 must always be ruled out. Lyme disease is caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi and is transmitted to humans through the bite of infected blacklegged Ixodes ticks. Relevant history includes tick exposure (e.g., camping, hiking in wooded areas). Goal is to remove tick as quickly as possible and it is imperative to not wait for it to detach. Ticks usually take approximately 2 to 3 days to transmit bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi saliva via bite; thus, prompt removal is a key component of infectious prophylaxis.

- Fungi: chronic course and can involve white lesions that breakthrough into the vitreous.

Figure 2: Slit-lamp visualization of the Ixodes tick larvae attached to the nasal conjunctiva of the patient's right eye, 1.5 mm posterior to the limbus. There was 2 + conjunctival injection and prominent episceral vessels. Adapted with permission from Kuriakose RK, Grant LW, Chin EK, Almeida DRP. Deer tick masquerading as pigmented conjunctival lesion. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2016;5:97-98. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2016.12.018

Lesson 2: Beware of red flags

Presence of red flags indicate possible atypical presentation which can progress quickly with severe vision loss and systemic morbidity. These include:

- First episode of uveitis in an elderly patient.

- Uveitis in patient with significant systemic illness.

- Uveitis in immunocompromised patients (e.g., malignancy, HIV/AIDS).

- Uveitis in patients with high-risk behaviors (e.g., illicit drug use).

- Hospitalized patients with new uveitis diagnosis (e.g., indwelling catheters increase risk of infection).

Lesson 3: disease prevalence and differential diagnosis

Use disease prevalence to narrow your differential diagnosis.

Remember that common diagnoses are most common!

In cases of anterior uveitis (e.g., iritis), most common causes are idiopathic, HLA-B27 associated disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis in pediatric patients, and anterior chamber reaction secondary to herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus.

With respect to posterior segment inflammation, the most common worldwide cause is Toxoplasmosis infection.

Anatomical location and differential diagnosis

Primary anatomical location

In uveitis, primary anatomical location of inflammation matters.

Primary location of inflammation allows one to organize differential diagnosis as follows:

- Anterior uveitis: iritis, cyclitis, iridocyclitis.

- Intermediate uveitis: inflammation of the posterior part of ciliary body and pars plana (far periphery of retina).

- Posterior uveitis: isolated inflammation of choroid (choroiditis) versus isolated retinal inflammation (retinitis). Primarily choroidal inflammation with secondary retina involvement (chorioretinitis) versus primarily retinal inflammation with secondary choroidal involvement (retinochoroiditis).

- Panuveitis: inflammation of the entire uveal tract (e.g., trauma, endophthalmitis).

Anterior uveitis

Idiopathic iridocyclitis is the most common cause of anterior uveitis.

In adults, the most common cause of anterior uveitis is idiopathic iridocyclitis, representing 10% of all uveitis cases.

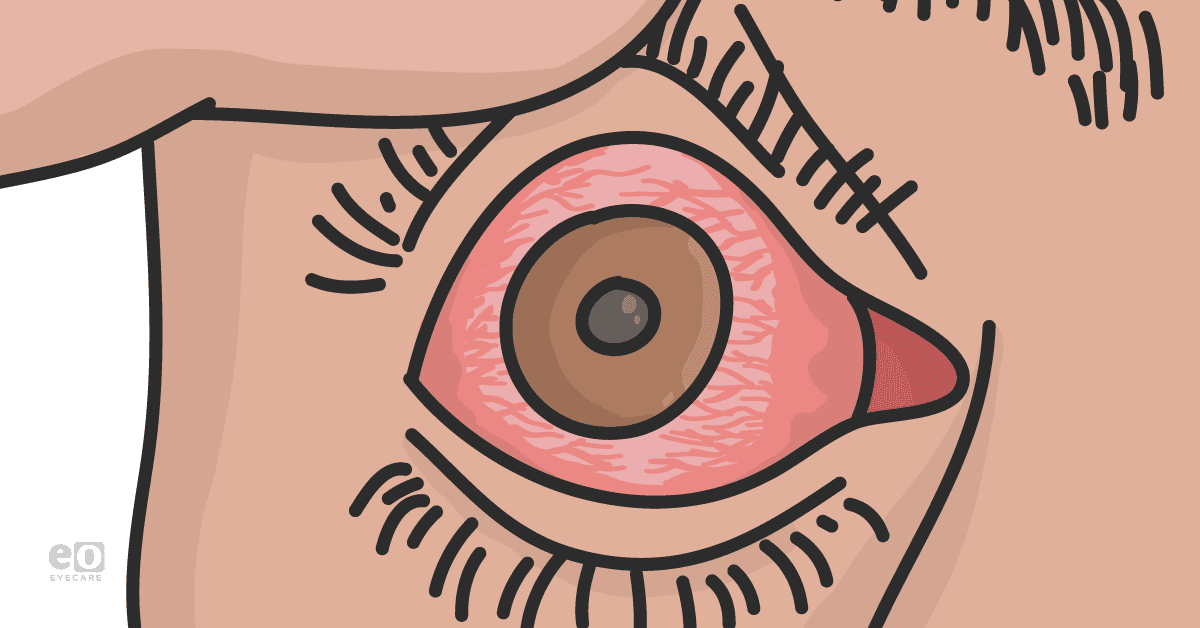

Figure 3: Presentation of idiopathic iridocyclitis with conjunctival injection, anterior chamber reaction, iris transillumination defects and posterior synechiae.

Intermediate uveitis

Pars planitis is the most common cause of intermediate uveitis.

Pars planitis, also known as idiopathic intermediate uveitis, is the most common cause of intermediate uveitis and represents 80 to 90% of cases involving the posterior ciliary body and pars plana as the primary anatomical inflammatory sites. Clinical signs include vitreous inflammation (vitritis, snowballs, snowbanks) in the absence of retinal findings. Patients may have a concomitant mild iritis in cases of pars planitis.

Figure 4: Presentation of pars planitis with vitreous inflammation consisting of snowballs and snowbanking over the pars plana.

Pars planitis typically presents during the ages of 5-15 years old and is bilateral in 80% of cases. Careful dilated depressed examination will reveal vitreous inflammation consisting of snowballs (vitritis) and snowbanks (vitreous inflammation over pars plana inferiorly). Associated signs include cataract with posterior synechiae, cystoid macular edema, epiretinal and epimacular membrane formation; severe cases can demonstrate peripheral neovascularization with vitreous hemorrhage and tractional components. In patients with pars planitis, vision loss occurs primarily from cystoid macular edema (50% of cases), cataract, neovascularization (10% of cases) and vitreous hemorrhage (5% of cases).

Differential diagnosis of intermediate uveitis is SIMPLE:

- S: sarcoid, syphilis

- I: inflammatory bowel disease (usually pediatric patients)

- M: multiple sclerosis (associated with periphlebitis)

- P: pars planitis (idiopathic)

- L: lyme, lymphoma

- E: etcetera (tuberculosis, Behçet’s disease (BD), Whipple, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada)

Figure 5: Presentation of intermediate uveitis with peripheral periphlebitis in a patient with multiple sclerosis.

Posterior uveitis

Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of posterior uveitis.

Toxoplasmosis, a form of infectious posterior uveitis, is the most common cause of posterior uveitis and represents 7% of all cases of uveitis. Toxoplasmosis gondii is a protozoan that typically presents as a focal area of white retinitis proximal to a pigmented scar with associated prominent vitritis. Management involves oral treatment with 800 mg sulfamethoxazole and 160 mg trimethoprim. Although oral and intraocular corticosteroids can be employed for inflammatory control, concomitant anti-protozoal coverage is necessary.

Figure 6: Classical presentation of posterior uveitis secondary to Toxoplasmosis with a focal area of retinitis proximal to a chronic pigmented scar.

Testing

Syphilis, tuberculosis, and Lyme

Uveitis workup always requires testing for syphilis, tuberculosis, and Lyme.

Always test for syphilis!

- Syphilis with uveitis implies neurosyphilis (central nervous system spirochete) which requires lumbar puncture and intravenous antibiotics.

- May present as optic disc swelling or yellowish translucent retinal spots or yellow plaques. Angiography will demonstrate vessel leakage in area of syphilitic plaques.

- Test with syphilis antibodies assay.

Figure 7: Presentation of posterior uveitis secondary to syphilis with optic disc swelling (left) associated with extensive leakage on angiography (right).

Always test for tuberculosis!

- Risk factors include history of travel to foreign endemic area and health care worker exposure.

- Tuberculosis can present as retinal vasculitis (Eales disease), serpiginous-like, posterior placoid type, posterior tubercles, anterior uveitis.

- Test with skin purified protein derivative (PPD) test (very sensitive but not specific) AND serum quantiferon assay (very specific but lower sensitivity). Serum quantiferon best for patients with history of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine or immunocompromised status; quantiferon serum testing can also be used as an indicator of active disease

- Management requires an infectious disease consultant.

Figure 8: Presentation of posterior uveitis secondary to tuberculosis infection with posterior pole plaques. Angiography displays characteristic early hypofluorescence followed by late hyperfluorescence.

Always test for Lyme!

- May be able to elicit history of being in wooded areas or history of skin targetoid lesion.

- Commonly associated systemic symptoms include arthritis and meningitis.

- Most common ocular finding is conjunctivitis.

- Optic nerve (optic neuritis and perineuritis, disc edema, ischemic optic neuropathy) and retinal (hemorrhages, exudates, exudative detachment, cystoid macular edema) involvement can be seen in uveitic forms.

- Test with Lyme titers assay.

Figure 9: Presentation of posterior uveitis (disc edema, focal retinitis) secondary to infection with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi in Lyme disease.

Conclusion

Uveitis remains a daunting and challenging disease area for ophthalmology residents and fellows. Although most cases of uveitis are idiopathic, the need to manage complex autoimmune diseases and infectious processes requires a careful, detailed and systematic approach to diagnosis. In this course, we have reviewed a modern approach to the diagnosis of ocular inflammation with direct emphasis on critical diseases and clinical pearls.